TISC is a two-week online sequential style CTF competition hosted by CSIT, where participants solve a series of 12 challenges. Over 1300 participants took on the challenges, with the top three levels of challenges having a cash prize pool of $10,000 each to be shared between participants who’ve successfully cleared the respective levels.

I was given the opportunity to create the challenge at level 7, a Web3 reverse engineering/binary exploitation challenge. I’ll be sharing the writeup, as well as source code and my thoughts, at the end of the blog post. You can check out the statistics for the ctf here. 17 people managed to solve my challenge; thank you friends.

Challenge

📘 Challenge description:

While scanning their network, you chance upon a tool that checks for the validity of a secret passphrase. You know that they use this phrase for establishing communications between one another, but the one you have is way outdated.

It’s time for an update.

Link to source code (including setup files, files given to the participants, and solution script)

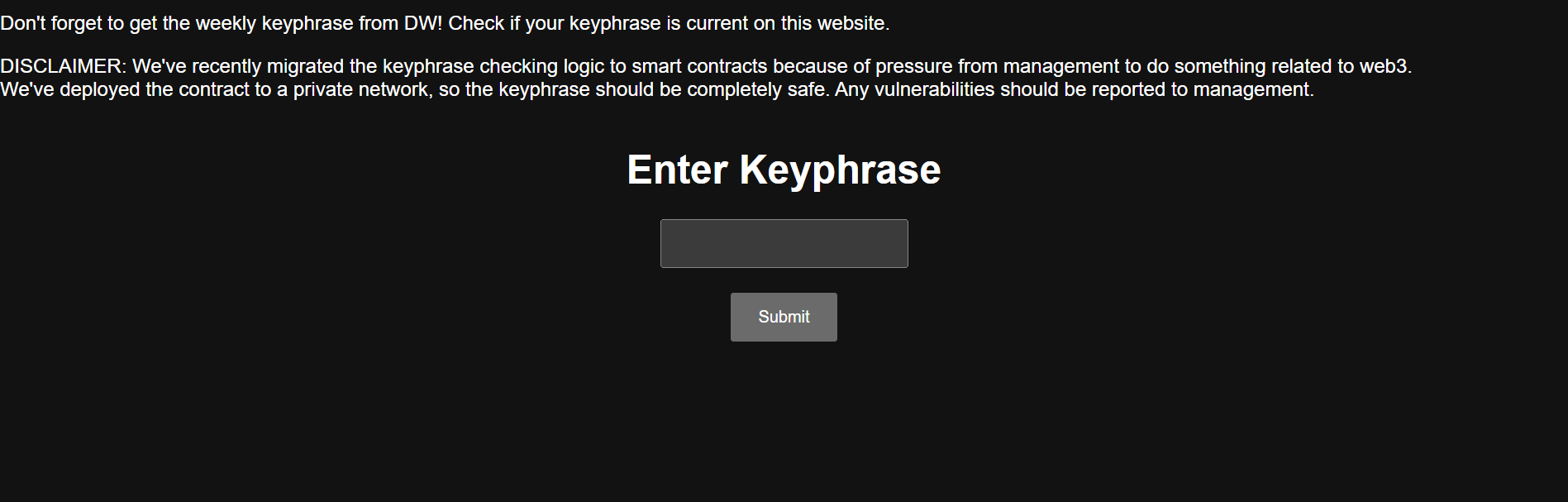

The website is stupid simple. It’s just one text input with a submit button, and if your passphrase isn’t correct, “Invalid” is flashed on the screen. Participants don’t actually know what’s displayed when the passphrase is correct so we’ll leave that as a surprise for later.

Writeup

TLDR

SSTI to information leak to side channel attack via gas usage

NLDR (Not long did read) - Stage 1: SSTI to information leak

Trivially, the input is vulnerable to SSTI. Using standard CTF techniques to enumerate the machine and achieve RCE will be futile as the only instance of the flag is stored on the private blockchain network. Also, there’s a WAF that blocks strings more than 32 characters long. This length check was honestly so I didn’t have to deal with any ABI shenanigans when calling the contract, but I’m glad it had the unintended effect of discouraging people from going down the SSTI rabbit hole.

@app.route('/submit', methods=['POST'])

def submit():

password = request.form['password']

try:

if len(password) > 32:

return render_template_string("""

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>Check Result</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Keyphrase too long!</h1>

<a href="/">Go back</a>

</body>

</html>

""")

# Rest of endpoint here

return render_template_string("""

...

""", response_data=response_data)

Looking at app/main.py, we can see that the whole of response_data is passed into Jinja’s context instead of just the output. The object format can be seen in server/connect_to_testnet.py:

{

"output": output,

"contract_address": setup_contract.address,

"setup_contract_bytecode": os.environ['SETUP_BYTECODE'],

"adminpanel_contract_bytecode": os.environ['ADMINPANEL_BYTECODE'],

"secret_contract_bytecode": os.environ['SECRET_BYTECODE'],

"gas": gas

}

We can leak all this information using the payload {{ response_data }}.

Stage 2: Reverse engineering the smart contract bytecode

From the previous stage, we get:

{'output': False,

'setup_contract_address': '0x5FC8d32690cc91D4c39d9d3abcBD16989F875707',

'setup_contract_bytecode': '0x608060405234801561001057600080fd5b5060405161027838038061027883398101604081905261002f9161007c565b600080546001600160a01b039384166001600160a01b031991821617909155600180549290931691161790556100af565b80516001600160a01b038116811461007757600080fd5b919050565b6000806040838503121561008f57600080fd5b61009883610060565b91506100a660208401610060565b90509250929050565b6101ba806100be6000396000f3fe608060405234801561001057600080fd5b506004361061002b5760003560e01c8063410eee0214610030575b600080fd5b61004361003e366004610115565b610057565b604051901515815260200160405180910390f35b6000805460015460408051602481018690526001600160a01b0392831660448083019190915282518083039091018152606490910182526020810180516001600160e01b0316635449534360e01b17905290518493849316916100b99161012e565b6000604051808303816000865af19150503d80600081146100f6576040519150601f19603f3d011682016040523d82523d6000602084013e6100fb565b606091505b50915091508061010a9061015d565b600114949350505050565b60006020828403121561012757600080fd5b5035919050565b6000825160005b8181101561014f5760208186018101518583015201610135565b506000920191825250919050565b8051602080830151919081101561017e576000198160200360031b1b821691505b5091905056fea2646970667358221220e0f8333be083b807f8951d4868a6231b41254b2f6157a9fb62eff1bcefafd84e64736f6c63430008130033',

'adminpanel_contract_bytecode': '0x60858060093d393df35f358060d81c64544953437b148160801b60f81c607d1401600214610022575f5ffd5b6004356098636b35340a6060526020606020901b186024356366fbf07e60205260205f6004603c845af4505f515f5f5b82821a85831a14610070575b9060010180600d146100785790610052565b60010161005e565b81600d1460405260206040f3',

'secret_contract_bytecode': '0xREDACTED',

'gas': 29307}

There are 3 contracts deployed to the network: Setup, AdminPanel, and Secret. Secret’s bytecode has been redacted, probably because it contains the keyphrase. We still have the bytecode from the other two contracts, however, and can see how our keyphrase is being checked.

Before going into reverse engineering, we can get a better idea of Setup by looking at the server files provided, giving us a better place to start.

uint256 deployerPrivateKey = DEPLOYER_PRIVATE_KEY;

vm.startBroadcast(deployerPrivateKey);

Setup setup = new Setup(address(adminPanel), address(secret));

console2.log("Setup contract deployed to: ", address(setup));

vm.stopBroadcast();

# server/contracts/script/Deploy.s.sol

passwordEncoded = '0x' + bytes(password.ljust(32, '\0'), 'utf-8').hex()

try:

gas = setup_contract.functions.checkPassword(passwordEncoded).estimate_gas()

output = setup_contract.functions.checkPassword(passwordEncoded).call()

Setup’s constructor function takes in two addresses, that of AdminPanel and Secret. It has another external function checkPassword(bytes32) that takes in the keyphrase and outputs a boolean.

We can pass Setup’s bytecode into any Ethereum Virtual Machine decompiler (this writeup uses free and publically available decompilers like heimdall and dedaub, but if you want to look at the disassembly that’s fine too, the contracts in this challenge are really small) and look at the output. Since the bytecode includes the constructor, only the deployment code appears at first:

uint160 ___function_selector__; // STORAGE[0x0] bytes 0 to 19

uint160 stor_1_0_19; // STORAGE[0x1] bytes 0 to 19

function function_selector() public payable {

...

___function_selector__ = MEM[MEM[64]];

stor_1_0_19 = MEM[MEM[64] + 32];

MEM[0:442] = 0x6080...;

return MEM[0:442];

}

We see the addresses of AdminPanel and Secret saved into EVM storage, and some bytecode getting returned from the function. This will be the deployed bytecode of Setup where our checkPassword function is. We can copy the string and decompile it once more:

bytes32 store_b;

bytes32 store_a;

function Unresolved_410eee02(uint256 arg0) public payable returns (bool) {

uint256 var_a = arg0;

address var_b = address(store_a);

uint256 var_c = 0x44 + (var_d - var_d);

uint256 var_d = var_d + 0x64;

uint224 var_e = 0x5449534300000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 | (uint224(var_f));

uint256 var_g = 0;

(bool success, bytes memory ret0) = address(store_b).call{ gas: gasleft(), value: var_g }(abi.encode());

...

}

bytes32 store_b is AdminPanel’s address, and bytes32 store_a is Secret’s. Function Unresolved_410eee02 is almost certainly checkPassword, and our keyphrase is being passed in as arg0. A call is being done on a function in AdminPanel using solidity’s ABI specification, which you can read here. Knowing how the ABI works is pretty much the crux of this stage since the AdminPanel contract has been obfuscated with a non-standard function selector and calldata retrieval method. Details of the CALL instruction are as follows:

| Stack Input | Description |

|---|---|

| gas | Amount of gas to send to the sub context to execute. The gas that is not used by the sub context is returned to this one. |

| address | The account whose context to execute. |

| value | Value in wei to send to the account. |

| argsOffset | Byte offset in the memory in bytes, the calldata of the sub context. |

| argsSize | Byte size to copy (size of the calldata). |

| retOffset | Byte offset in the memory in bytes, where to store the return data of the sub context. |

| retSize | Byte size to copy (size of the return data). |

In the evm, when a call is made to a smart contract, both the function to call and its arguments are passed as one long bytestring referred to as args. The first 4 bytes of this bytestring are reserved for the function signature, which specifies the function to call within the contract. All data after the signature are the function arguments, and each argument takes exactly 32 bytes. This is, of course, assuming that the contract was compiled with these standards in mind. The AdminPanel contract was not.

Let’s reverse engineer it along with Setup to help us understand how the call is done. Removing the constructor and decompiling is finnicky with most online tools (as the instructions were written manually), but luckily this contract is tiny and the disassembly is a mere 88 instructions long (as the instructions were written manually). Simply referring to the evm opcode reference and tracing the stack is enough to debug most problematic decompiler outputs and give you this function:

function (bytes4 function_signature, uint256 varg1, uint256 varg2) public payable {

require(0x544953437B == args[0:5]);

require(0x7D == args[16]);

v0 = varg2.delegatecall(0x66fbf07e).gas(msg.gas);

i = num_of_chars_correct = 0;

while (1) {

if ((keccak256(0x6b35340a) << 152 ^ varg1)[v1] == v0[v1]) {

num_of_chars_correct += 1;

}

i += 1;

if (i == 13) {

return num_of_chars_correct == 13;

}

}

}

It’s apparent that this function is doing a character-by-character comparison of two strings. The first string is the first argument to the function XORed with some key, and the second is the result of a delegatecall to the contract at the address specified by our second argument. Cross-referencing the Setup contract, it’s clear that the second argument is the address to the Secret contract, and the first is our submitted keyphrase. Note that there are also checks on the args bytestring as a whole at the start of the function

The args used to call AdminPanel would therefore have to look something like this:

| Size | Data | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 bytes | 0x54495343 | Function signature |

| 32 bytes | 0x7B??????????????????????7D000000… | Keyphrase |

| 32 bytes | 0x????… | Address of Secret contract |

Chaining all these arguments together into the ABI encoded bytestring, we get:

0x544953437B??????????????????????7D0000...??????...

Note how the function signature and the keyphrase form a contiguous section that decodes to TISC{???????????}. This is obviously the flag, but we can’t look at the Secret contract to see what its being compared to. What now?

Stage 3: Side channel attack using calculated gas estimate

This premise, combined with the odd character-by-character comparison between the strings instead of using the EQ instruction, intuitively tells us that there’s some form of blind attack we need to find some side channel for, but coming up with a definite solution is tricky. The key thing to note here is how the evm calculates gas prices for each transaction.

When you make a transaction or call a function, there are gas fees involved that are paid to the validators. How this gas fee is calculated is based on the evm instructions ran per transaction. Each opcode corresponds to a set gas value, and throughout the execution of the code, these gas values are tallied up to give a numerical estimate for the computational cost of the transaction. This number is then multiplied by the current cost of gas to get the final fee.

In the debugging information we managed to leak earlier, we can see the total gas value our transaction has used. The interesting thing about this value is that it changes based on the path the transaction takes down the control flow of the program, as the number of instructions ran through varies. We can use this idea to do a side-channel attack using the gas value as our metric.

When a successful character comparison is done, the control flow deviates and runs one extra line of code:

num_of_chars_correct += 1;

In the disassembly output, this deviation corresponds to these instructions:

0x70: JUMPDEST 1 gas

0x71: PUSH1 0x1 3 gas

0x73: ADD 3 gas

0x74: PUSH2 0x5e 3 gas

0x77: JUMP 8 gas

which adds up to 18 gas total. This means that for every correct character in our keyphrase, the gas value will increase by 18. Submitting

{00000000000}{{ response_data }}

and reading the gas value gives us 33365, but submitting

{g0000000000}{{ response_data }}

gives us a value of 33383, telling us that our flag starts with g. We can do the same to all the characters in the flag with the script in solve.py to get the flag!

TISC{g@s_Ga5_94S}

Thoughts

I came up with the idea of doing a gas side channel attack in my sleep.

I was stressed the hell out coming up with an idea to best all other previous CTF challenges I’ve made thus far (and I’ll be the first to say they’re all really good challenges), and I was convinced that EVM was the way to go since I’d been doing so much research into it lately, but nothing really clicked. I tried making an EVM pwn before this, but I had to do so many weird things that people wouldn’t normally do to make a pointer overwrite possible, and I don’t like it when CTF challenges just do the most unbelievable things that no sane developer would do just to get a point across.

It was a real eureka moment for me, using the gas estimate as a means to count instructions. I don’t think I’ve seen this exploit being documented online before (partially because not a lot of people deploy contracts to private networks), and it was a good opportunity to introduce the concept of the evm and gas calculations to participants. I was so excited (ask anyone in the office on that day) since I had been struggling on a challenge idea for literal weeks.

Making the challenge

If you look at the contracts’ source code, you’ll notice that instead of solidity, they’re written in an evm-level language called Huff. I’ll put the contract code here for convenience:

/* AdminPanel.huff */

/* Interface */

#define function checkPassword(address,bytes32) nonpayable returns (bytes32)

/* Methods */

#define macro CHECK_PASSWORD() = takes (0) returns (5) {

0x04 calldataload // [password]

// XOR with secret key

0x98 // [length, plaintext]

0x6b35340a 0x60 mstore // [length, plaintext]

0x20 0x60 sha3 // [hash, length, plaintext]

swap1 shl xor // [xoredPlaintext]

0x24 calldataload // [secretAddr, password]

// Store function signature in memory

0x66fbf07e 0x20 mstore

// Retrieve password from external contract

0x20 0x00 0x04 0x3C dup5 gas delegatecall

pop 0x00 mload // [secret, secretAddr, password]

// Push itercount and correctCount to the stack

0x00 0x00 // [correctCount, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

iterativeCheck:

dup3 dup3 byte // [secretNth, correctCount, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

dup6 dup4 byte // [flagNth, secretNth, correctCount, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

eq correctChar jumpi // [correctCount, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

iterativeCheckAfterJump:

swap1 0x01 add // [itercount++, correctCount, secret, secretAddr, password]

dup1 0x0D eq end jumpi // [itercount, correctCount, secret, secretAddr, password]

swap1 // [correctCount, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

iterativeCheck jump

correctChar:

0x01 add // [correctCount++, itercount, secret, secretAddr, password]

iterativeCheckAfterJump jump

end:

dup2 0x0D eq // [correct?, itercount, correctCount, secret, secretAddr, password]

0x40 mstore // [itercount, correctCount, secret, secretAddr, password]

0x20 0x40 return

}

#define macro MAIN() = takes (0) returns (1) {

// Check for flag format

0x00 calldataload // ["TISC{###########}"]

dup1 0xD8 shr // ["TISC{", "TISC{###########}"]

0x544953437B eq // [1, "TISC{###########}"]

dup2 0x80 shl 0xF8 shr // ["}", 1, "TISC{###########}"]

0x7D eq // [1, 1, "TISC{###########}"]

add 0x02 eq checkPassword jumpi

0x00 0x00 revert

checkPassword:

CHECK_PASSWORD()

}

/* Secret.huff */

/* Interface */

#define function secretP1ssp00r() nonpayable returns (bytes32)

/* Methods */

#define macro SECRET_P1SSP00R() = takes (0) returns (0) {

// Store "{g@s_Ga5_94S}" encrypted in memory for return

0xDEAF50391118A37595C50AC9F700000000000000000000000000000000000000 0x00 mstore

// End Execution

0x20 0x00 return

}

#define macro MAIN() = takes (0) returns (0) {

// Identify which function is being called.

0x00 calldataload 0xE0 shr

dup1 __FUNC_SIG(secretP1ssp00r) eq secretP1ssp00r jumpi

0x00 0x00 revert

secretP1ssp00r: // So that people cant find this on 4 byte signature databases

SECRET_P1SSP00R()

}

The reason for this is that I was running out of time to submit the challenge, so I couldn’t draft an applicable control flow graph that solidity would compile to before the deadline. Because of this, I chose to implement the most textbook example of a function vulnerable to side channel attacks, which involved writing the instructions manually in huff since I didn’t have time to deal with compiler shenanigans.

Next time I make this challenge, it’ll be a huge CFG with multiple paths so you actually have to do some math to arrive at the solution.